Overview

Shoulder instability develops in two different ways: traumatic onset (related to a sudden injury) or atraumatic onset (not related to a sudden injury). Understanding the differences is essential in choosing the best course of treatment. As a rule, the patient with atraumatic onset instability has general laxity (looseness) in the joint that eventually causes the shoulder to become unstable, whereas traumatic onset instability begins when an injury causes a shoulder to develop recurrent (repeated) dislocations.

Atraumatic shoulder instability, also called multidirectional instability (MDI), is described as laxity of the shoulder's glenohumeral joint in multiple directions.

What does the inside of the shoulder look like?

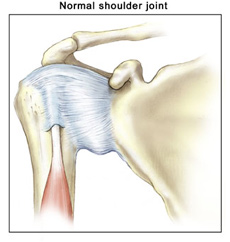

The shoulder is the most mobile joint in the human body with a complex arrangement of structures working together to provide the movement necessary for daily life. Unfortunately, this great mobility comes at the expense of stability. Four bones and a network of soft tissues (ligaments, tendons, and muscles), work together to produce shoulder movement. They interact to keep the joint in place while it moves through extreme ranges of motion. Each of these structures makes an important contribution to shoulder movement and stability. Certain work or sports activities can put great demands upon the shoulder, and injury can occur when the limits of movement are exceeded and/or the individual structures are overloaded.

What is atraumatic shoulder instability? Atraumatic shoulder instability develops in patients who have increased looseness of the supporting ligaments that surround the shoulder's glenohumeral joint. The laxity can be a natural condition (present from birth) or a condition that has developed over time. Many patients with MDI are active in overhead sports (such as gymnastics, swimming, or throwing) that repetitively stretch the shoulder capsule to extreme ranges of motion.

Atraumatic shoulder instability develops in patients who have increased looseness of the supporting ligaments that surround the shoulder's glenohumeral joint. The laxity can be a natural condition (present from birth) or a condition that has developed over time. Many patients with MDI are active in overhead sports (such as gymnastics, swimming, or throwing) that repetitively stretch the shoulder capsule to extreme ranges of motion.

The glenoid (the socket of the shoulder joint) is a relatively flat surface that is deepened slightly by the labrum, a cartilage cup that surrounds part of the head of the humerus. The labrum acts as a bumper to keep the humeral head firmly in place in the glenoid. It is also the attachment point for important ligaments that stabilize the shoulder. These ligaments often become stretched out with MDI, allowing dislocation or subluxation (an incomplete or partial dislocation) to occur. The increased motion of the joint can lead to repetitive microtrauma (small injuries), producing tears of the labrum or rotator cuff.

MDI patients will often have increased ligament laxity in many joints. Hyperextended knees, elbows, and a self-described history of being "double-jointed" are common. These patients often have multidirectional laxity in both shoulders. Because many athletes with MDI are quite successful in their sports, there is a debate about whether laxity improves performance or is caused by repetitive stretching during athletic activity.

Multidirectional Instability >> Symptoms

What are the signs and symptoms of MDI (Multidirectional Instability) or atraumatic shoulder instability?

MDI problems are generally related to recurrent episodes of dislocation. - Repeated subluxations often cause patients to be apprehensive about performing certain daily activities.

- Vague symptoms are described, such as an indistinct pain in the shoulder. Patients may sense that something is not quite right with the shoulder during activities when the arm is in certain positions.

- There may be pain caused by inflammation in the joint.

- Patients may show signs of labrum and/or rotator cuff injuries that have resulted from the increased movement in the joint.

Multidirectional Instability >> Diagnosis

Diagnosis

How is atraumatic shoulder instability diagnosed?

A thorough history and physical examination are the keys to the diagnosis and treatment of MDI (Multidirectional Instability). The classic findings are:

- a history of generalized laxity.

- no history of a forceful dislocation event.

- a history of recurrent episodes of instability.

The patient's history may reveal a recent injury, an obvious dislocation, or a change in sport or training that has led to instability in a previously healthy shoulder.

A general examination of joint mobility is very helpful. By moving the arm around in several positions, the doctor can evaluate full shoulder motion. Multidirectional laxity may be present in both shoulders even though only one may be bothersome to the patient. A patient with MDI has an increase in glenohumeral translation (shoulder joint movement) in multiple directions, and symptoms can be recreated in one or more directions. More than 2 cm of movement during the sulcus test suggests the presence of MDI. The diagnosis of MDI should be based on this result combined with the evaluation of overall shoulder motion and the symptoms triggered when the doctor moves the arm in several directions.

Further evaluation may include some form of visual study of the shoulder.

- X-rays are always obtained, primarily to rule out any associated injuries that would require treatment. Occasionally the images reveal a congenital (present since birth) abnormality that may be contributing to the instability.

- An MRI (Magnetic Resonance Image) can reveal other sources of the shoulder pain that may require more than a rehabilitation program alone for successful treatment.

- An arthroscopy allows the surgeon to visually evaluate the structures of the glenohumeral joint using a tiny fiberoptic instrument. Other related injuries may be revealed since increased movement and repetitive trauma in the joint can lead to injuries of the labrum and partial thickness rotator cuff tears. With arthroscopy, these injuries can be treated at the time of the examination, and the patient may go on to achieve a pain free shoulder with a rehabilitation program.

Multidirectional Instability >> Treatment

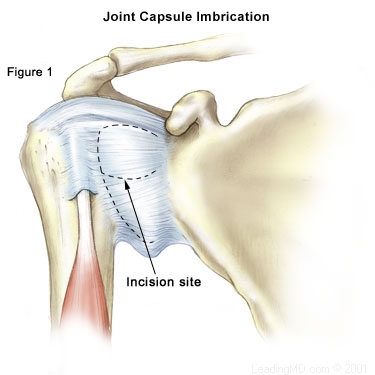

| How is MDI (Multidirectional Instability) treated? The treatment for MDI must be individualized for each patient. Non-Operative Treatment Most patients with MDI can be treated non-operatively with a physical therapy program that emphasizes muscular rehabilitation. Rehabilitation focuses on strengthening the rotator cuff muscles and periscapular muscles (those around the scapula). Strengthening these muscles provides dynamic stability to the joint, which is especially important when the static stability provided by the ligaments is lacking. The vast majority of patients (about 90%) who follow a rehabilitation program diligently for at least six months will achieve pain relief. Those who continue with a daily or weekly exercise program as outlined by the doctor are most likely to have a successful recovery. Athletes may also benefit from sport-specific rehabilitation that includes technique evaluation and modification. Often this type of program can help eliminate faulty technique that may have led to the development of symptoms. Patients who do not get relief from symptoms with a physical therapy program are a treatment challenge. Only about 70-80% of these patients eventually achieve long-term stability, with 60-70% reaching the level of athletic participation they enjoyed prior to the instability. Operative Treatment The most challenging patient to treat surgically is the athlete whose symptoms continue following a rehabilitation program. Often athletes are successful in their sport because of increased laxity in the joint; so surgical intervention should only be considered when the patient has a thorough understanding of MDI, and is aware that stability with surgical correction is always achieved at the expense of motion. Patients who can voluntarily dislocate the shoulder are poor surgical candidates; surgery is rarely successful for them.

Traditional Approach

Arthroscopic Techniques

|

Multidirectional Instability >> Overview

Non-Operative RecoveryRecovery from MDI (Multidirectional Instability) is a long process that usually requires a six-month physical therapy rehabilitation program. If this succeeds, an ongoing maintenance program to prevent the return of instability symptoms is often necessary. If six months of physical therapy has not controlled the instability, surgery may be indicated.

Operative Recovery

Following surgery:

- For the first 4 to 6 weeks, the patient usually wears a sling to protect the repair as it heals.

- During this time of immobilization, elbow and wrist motion are maintained with gentle range of motion exercises.

- Once the initial healing process is complete, the patient begins a very slow and progressive physical therapy rehabilitation program to restore motion and eventually strengthen the shoulder.

- Patients who have had open surgical procedures are put on an exercise program designed to protect the subscapularis muscle from injury. (This muscle was detached during the procedure to give the surgeon access to the joint capsule and then reattached at the end of the procedure.)

- Patients who undergo an arthroscopic thermal stabilization treatment require a longer period of immobilization (often up to 8 weeks) to allow scar tissue to replace the thermally treated tissue. This scar tissue formation is essential to the success of this procedure, as the thermally treated tissue is at risk of stretching.

- Full participation in sports is generally restricted for 9 to 12 months following a repair.

Multidirectional Instability >> FAQs

What is MDI?MDI refers to a multidirectional laxity of the shoulder joint with associated instability. The instability generally results from stretching of the shoulder's supporting ligaments, which leads to increased movement of the glenohumeral joint.

Will physical therapy succeed?

Research suggests that many patients (80%) will improve with physical therapy alone. The patient's diligence and commitment to a daily maintenance program is required for the best chance of success.

How much motion loss will I experience if surgery is needed to stabilize my shoulder?

Motion loss varies. The normal range of shoulder motion at 90 degrees of abduction (elbow pointing away from the body) is from 80-120 degrees of external (outward) rotation (the higher number is seen in patients who have developed increased motion for throwing sports). After a surgical stabilization, a stable shoulder will have on average about 90 degrees of external rotation at 90 degrees of abduction. Preliminary results show that arthroscopic procedures may reduce motion loss, but these are still being evaluated.

If I don't want a big incision, can this procedure be performed arthroscopically?

Arthroscopic techniques continue to evolve and improve. The short-term follow up data suggests that the success rates of arthroscopic repairs may equal those of open procedures. Although the initial results are very encouraging, further long-term studies are required to validate them.

References